(An essay for an Environmental Communication course)

Roughly a year ago I started rock climbing outdoors. Little did I know that doing this would change the course of my life forever and would have me utterly addicted to the sport. Yet, it is not just the act of climbing that lures me back into the mountains time after time to ascend the rock. Mysteriously, it is the rock itself that continues to bring me back.

I started climbing in the gym but after my first proper outdoor session, I never stepped foot back inside one again. There’s something about the mountain air on your skin as you’re suspended dozens of feet off the ground on a cool, gigantic rock face that is enchanting. At the end of each climbing session, however tired you may be, you are left with an unquenchable thirst for more – to come back the next day and get after it once again. It can be cold or hot, windy or even rainy, but when you’re up on that rock face you cannot feel any of that external stimuli. You become the rock in the sense of how fortified your psyche is at that present time. It’s as if you are you are the same with that rock. Like the rock is climbing itself, as silly as that may sound.

Take for example rock climbing in the desert. Out there, beyond the furthest reaches of civilization, you are on your own, at the will of the elements, far from the likes of man. Here, survival comes as intuitively as the path you walk through the desert sands amongst the junipers and cacti. The desert is as enchanting as it is empowering, and when you throw climbing in the mix it’s taken to a whole new level.

On the way to the desert crag in which I am walking towards to climb, my feet somehow know to guide me in the path of least resistance and most shade, if there is any at all. I flow through the desert tides with ease, like a sailing vessel harnessing a big wind. Meanwhile, my eyes are locked and focused up ahead; my neck slightly canted upwards as I stare at the giant wall I am about to ascend with gear and my climbing partner. The closer I get to this rock the more alive I feel. My heart beats faster, my skin perspires a little more, my throat muscles contract – I am thirsty, but the thirst I have is not the kind that can be quenched by liquids. I crave this rock how desert succulents crave water. Yet, when I am geared up and ready to climb this big wall – which I know may take several hours and use up all the energy I came here with - I fall into a state of unexplainable calmness.

Some would call it tranquility. As my mind becomes still, my breathing slows down, and I am only focused on the rock in front of me. The smooth feel of the desert sandstone becomes ever more prominent as my sense of touch is heightened, along with my other senses. My vision becomes sharper as my eyes start to see where my next moves on the wall will be, even though my mind doesn’t seem to be giving it much thought. My ears tune in to the sound of my hand and foot placements on the wall and to the sifting of the sand on the rock. I hear the breeze grow in ferocity the further I ascend, like a melody that’s older than time itself. This same wind cools my body somehow promoting an energized sensation only adding to my stamina. I keep climbing.

My mind is as still and as silent as the rock that is currently holding my life. If I stop and look down I can see the progress I’ve made. My climbing partner now looks like an ant on the desert floor below. I start to feel a tingle of fear trickle down my spine. I grip the crag evermore tightly for a second only to have this fear be absorbed by the rock allowing the stillness to return. My hands and feet start to move on their own again and I am re-submerged in a state of flow.

On this desert crag, I forget who I am. I forget what I am. I am just there – I just am. I am an extension of the rock. It’s an empowering feeling that is counterintuitively relaxing at the same time, in a way I’ll never truly understand. As I continue to climb and place gear, I may stop to catch my breath for a moment. This is when I notice the inhabitants of this crag and the desert with whom I am currently sharing.

I spot some grass growing in the rock, a hundred feet up off the ground. I wonder: how does this living entity thrive here, in the scorching heat of the desert, way up on this unforgiving rock? How does it survive, day in and day out? Besides the heavy load of water I brought with me, I haven’t seen the stuff for miles around. Yet, as fortified as the rock in which it is growing out of, this little desert shrub lives on.

Further captivated, I examine the shrub on the wall and realize it is not the only one besides me up here. There are insects crawling around. There is bird poop on the rock next to me. I can begin to see the entire universe that comprises this rock come into play, made up of an unthinkable number of organisms – from the grass to the insects to the birds flying around it and nesting and so forth. Above, like the stars in the night sky comprising the universe in which we live, below is no different. As above, so below, a wise man once said. It all starts to make sense now. I close my eyes and picture this series of infinite universes within themselves start to come into play. The wind picks up into a howl and I breathe in deeply, realizing that I am not apart from this desert world in which I’ve found myself. I am this desert world, I am the wind howling. I realize that as I breathe in the crisp, untainted desert air, in a way I am actually breathing in my self. And I smile.

My climbing partner calls from below and asks if I’m doing alright. I realize that I’ve paused and had my eyes closed for longer than I intended to. I shout down a phrase of reassurance, scan my beautiful surroundings from up high one more time, thanking it for its existence and its beauty. I look upwards and commence climbing once again, going for one last push to the top of the rock, that along with my rope and gear has held me on this existential journey up it.

As I near the top, I realize that I am sweating profusely because my fingertips are losing their grip on the rock which has now become slick with the grease from my hands. I put some more climbing chalk on my fingers which I now connect to the fact that it is just as much from the earth as the crag that I’m climbing. What a strange thought to pop into my head, I think to myself, especially since the amount of genuine thoughts I’m having up here is undoubtedly limited by the state of flow I’ve found myself immersed in. A couple more big leg pushes with some good handholds and I find myself at the end of the climbing route, surprised. I’m surprised that the route is now over as if I hadn’t expected it to ever end. I am pleasantly surprised yet almost disappointed that there isn’t more rock to climb, that it just ends here at the top. Strange it feels to have climbed it. Because although I may have spent several hours climbing this tall crag lost in the mystery of the desert, the climb itself had ended just as quickly as it had begun.

I realize now that this is probably how my entire life will feel once I’m at the end of it, as I know now that everything in this realm of the living is temporary. I stop to look around and only now can I comprehend how far of a distance I’ve traveled vertically up this rock. I’m impressed. Not with myself moreover, but with the rock, I have just climbed, and the exquisite desert it is in. That’s when my favorite part of the entire experience finds me. Directly above me, close enough to lock eyes with the feathered beast, I notice a large hawk soaring in the glow of the afternoon sun.

The hawk is soaring above me in circles looking as magnificent as anything I have ever seen. The raptor is coasting on thermals, going up, down, and around, perplexed on the desert floor below it. We notice each other. It starts to feel as if this entire day spent climbing up this incredible wall that has empowered me into temporarily being the most powerful, in-tune version of myself, has led up to this moment. It’s led to this somewhat important seeming encounter with this eternal keeper of the desert. We communicate with one other, but not in words; not in any tongue or not with any way of thinking – at least, not in the conventional or human sense. I can’t help but be flooded with an innate sense of appreciation as if the hawk was channeling to me, showing me the beauty of his land of which I am a humble visitor.

Then I think back to the climb I have just completed. It’s like climbing this rock was an entry exam granting me access into the eternal realm that the hawk resides. By gaining acceptance, I briefly get to step inside his domain. I unfocus my eyes to try and take it all in - the hawk, the crag, the wide-open sky, the wind; but I can’t. It’s all too much to absorb. Instead, I allow this overpowering sense of gratitude to flow through me once again. However, I don’t grip on to this feeling, like the rock that brought me up to this point in the desert. No instead, I let it go. I let go of the last sliver of human intention and I surrender to this sense of gratitude. For it’s as though the desert is trying to get back in touch with its self that’s hidden deep within me. And I let it.

Reflection

By the time we both got done climbing this huge wall, packed up our gear and started to head back through the desert landscape towards the vehicle to head home, the sun was setting. It was on this walk back that I tried to process everything that had just taken place in this outer-worldly beautiful and enchanting area of the desert which we just climbed. However, I had a hard time doing so because it was all too much.

I try to replay the events of the day and the climb in my head, focusing on the best parts of it. Like the hard parts of the climb, staring at the grass growing on the rock, or my encounter with the hawk at the top. I try to relive it, to enjoy it again as fully as I did when it was happening. But I don’t find much success. As thankful as I am and as good as I feel about all of it having happened, I don’t understand why or how all these things came to be. I especially don’t understand the reasons why I felt this way, or why I feel this way now. Why I had these sort of connections, and how my now altered brain chemistry had played into it all. Which is when I wonder: perhaps I was never meant to understand these things at all? Maybe I was just meant to live them? To enjoy them.

This shoots me off into an even deeper rabbit hole of thought about the nature of life itself, and my place in the universe. I question whether we as humans are meant to understand these questions, or even be asking them. Maybe, we aren’t. Maybe, we are just meant to live our lives and experience this ride we call life, and that’s as far as it goes. Maybe the purpose of life is inherently simple; and that is, to just live it!

The older I get and the more I learn, the less I know. However, the older I do get, the more comfortable I become with not knowing because I can start to accept that I actually don’t know anything at all. And that’s fine by me. Sure, I still plan to learn as much as I can until I have to leave this world, but I can now accept that there are some things I probably just won’t ever know or fully understand. I could go my whole life trying to find answers to life’s unanswerable questions. But I could also just accept that I don’t know, that I won’t ever fully know, and proceed to just live my life, happily. Otherwise, the alternative is to die consumed by these ponderings in a disturbed sort of way, as if I had failed by not finding the answers. Yet, I feel as though the hawk or the desert do not care for me to find these answers. Because they don’t even care about finding the answers themselves.

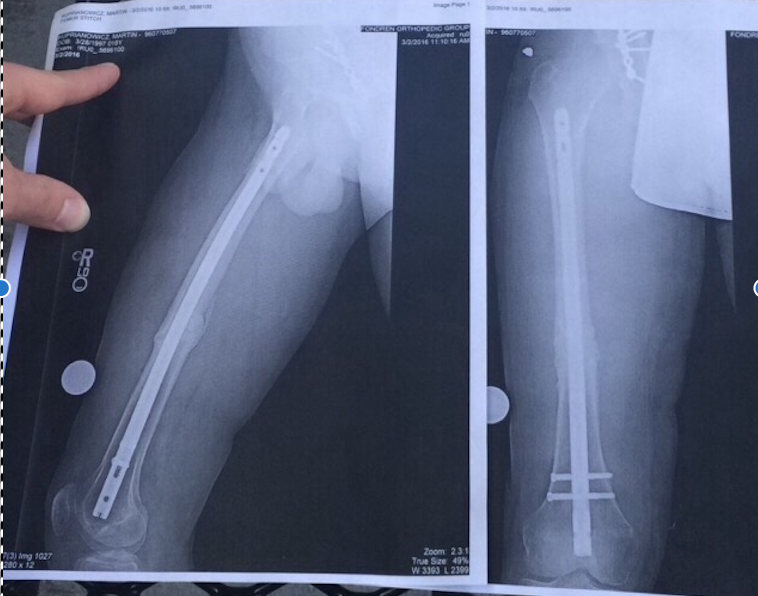

There's a lot of metal in this body now...

There's a lot of metal in this body now...

The percent change in average ski season lengths by 2050. Credit:

The percent change in average ski season lengths by 2050. Credit:  Snow droughts are periods of abnormally low snowpack for the time of year. Credit:

Snow droughts are periods of abnormally low snowpack for the time of year. Credit:

Skiing in the rain is not fun for skiers and not profitable for ski resorts. Credit:

Skiing in the rain is not fun for skiers and not profitable for ski resorts. Credit:  Skiing may be limited to high elevation mountain ranges in the future. Credit:

Skiing may be limited to high elevation mountain ranges in the future. Credit:

Can we save the future of skiing? Credit:

Can we save the future of skiing? Credit:  On average, 40 feet of snow falls on Whitewater every year. Credit:

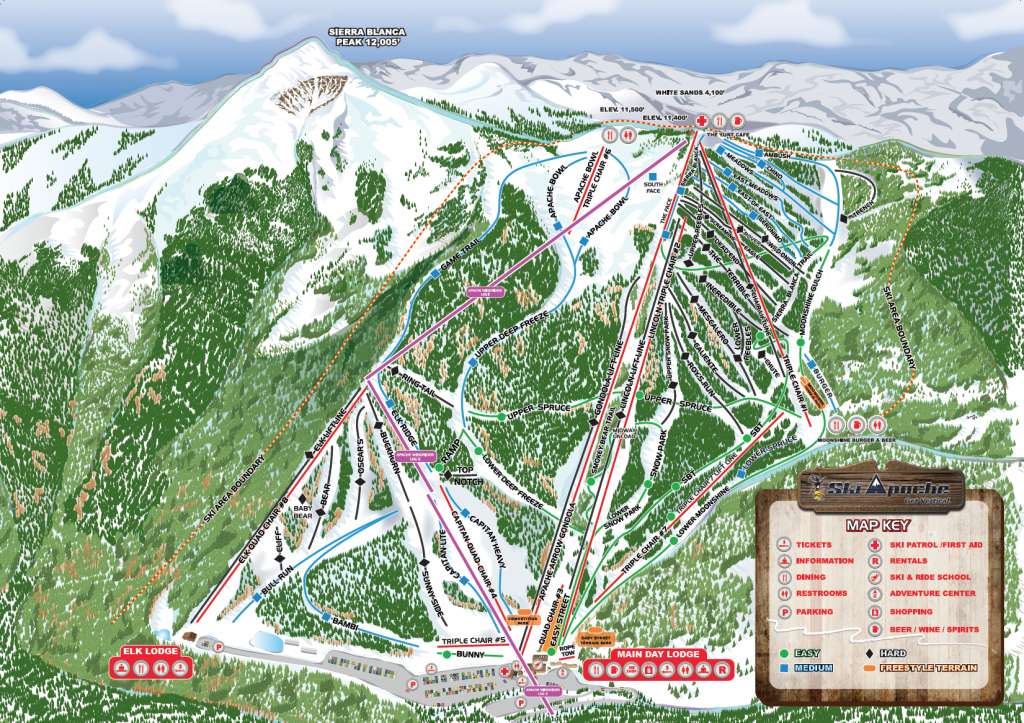

On average, 40 feet of snow falls on Whitewater every year. Credit:  Whitewater Ski Resort trail map. Credit:

Whitewater Ski Resort trail map. Credit:  Nelson, British Columbia - where powder skiers die and go to heaven. Credit:

Nelson, British Columbia - where powder skiers die and go to heaven. Credit:  Steep and deep. Credit:

Steep and deep. Credit:

Got what it takes to be a Whitewater patroller?. Credit:

Got what it takes to be a Whitewater patroller?. Credit:  Tourist skiers - often labeled as "Jerries" - help to create the bulk of the revenue that ski areas make per season. Image:

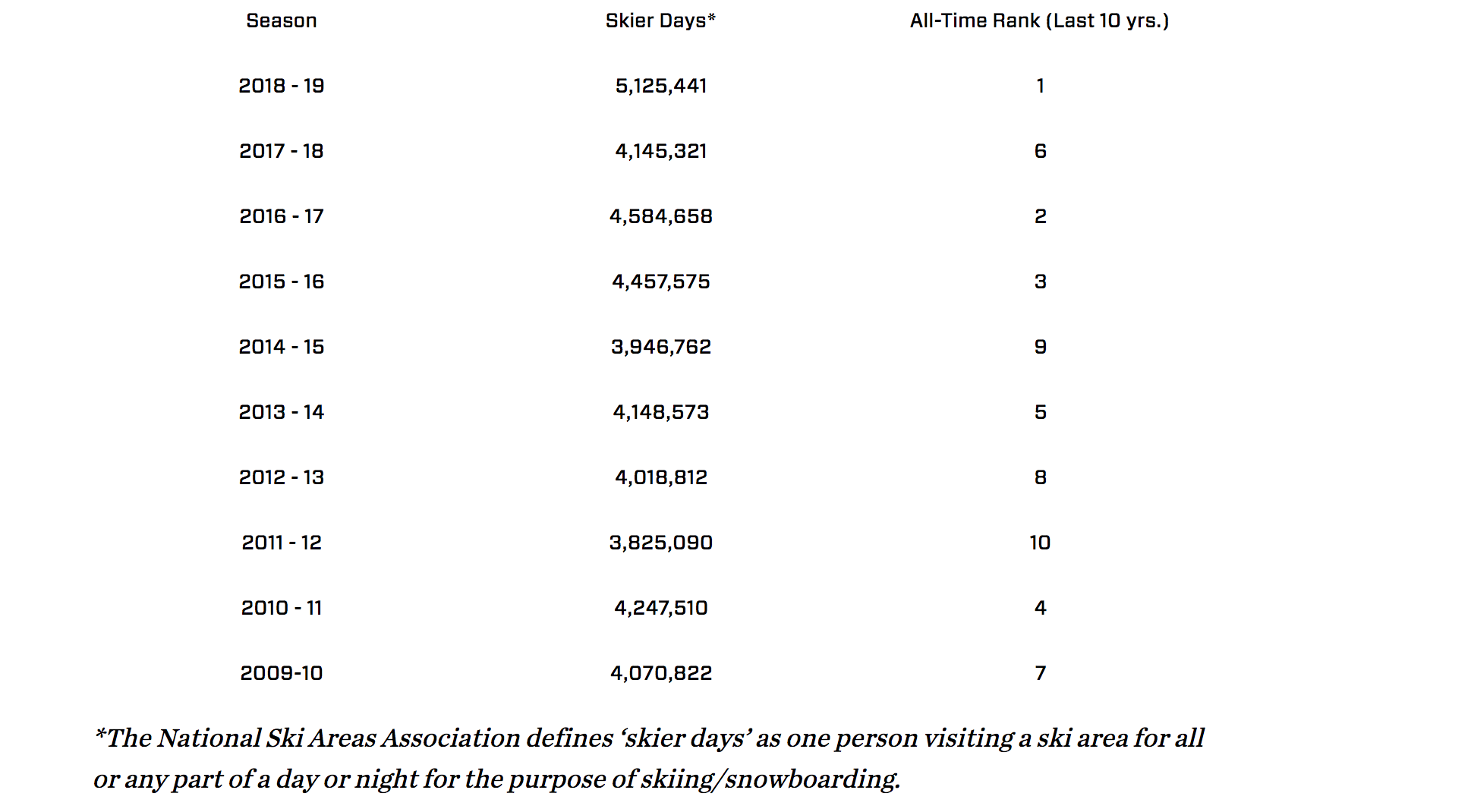

Tourist skiers - often labeled as "Jerries" - help to create the bulk of the revenue that ski areas make per season. Image:  Utah Skier visits by year.

Utah Skier visits by year.  The Ikon and Epic mega passes are increasing the revenue stream for the ski industry. Image:

The Ikon and Epic mega passes are increasing the revenue stream for the ski industry. Image: Image:

Image:

Jerry ready to send. Image:

Jerry ready to send. Image: